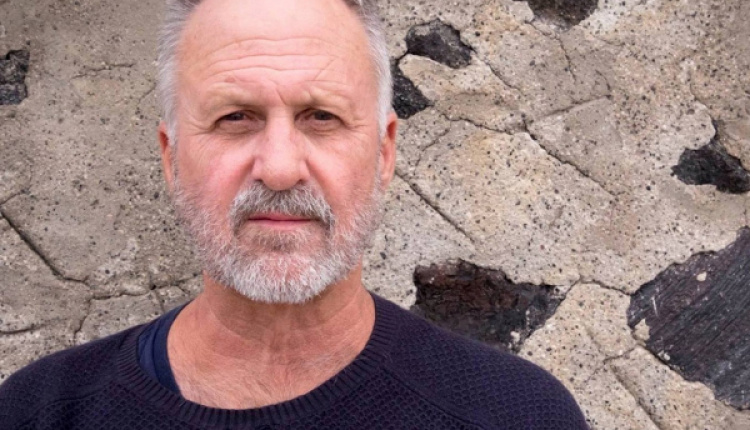

Writing With Purpose: Timothy Jay Smith On Greece, Social Justice & Storytelling

- by XpatAthens

- Thursday, 19 June 2025

by Angeliki Vourliotaki

by Angeliki VourliotakiAfter reading Fire on the Island, a suspenseful, heartfelt novel set in a Greek village, I was immediately intrigued by the man behind the story. My review barely scratched the surface of what Timothy Jay Smith brings to the page, and I couldn’t help but want to learn more about this fascinating writer and person.

So, we sat down for a long and heartfelt conversation. Timothy opened up about his life, his work, and his enduring bond with Greece. From planting tens of thousands of trees in Tanzania to founding a prize for political theater, to crafting layered characters drawn from real people, he offers the kind of perspective only a true global citizen can.

We began with the big question...

Q: For someone who isn't familiar with you or your background, how would you describe yourself as a writer and as a person?

That's a big question to start with! At a young age, I developed a social consciousness that would define my career and eventually my writing. Before I decided to become a full-time writer, I worked all over the world on projects to help low-income people, including in the United States, where we had a national program called the War on Poverty. When I was young and right out of college, I was able to get work that really allowed me to help others through different projects. So I guess I’m pretty compassionate in that sense.

When I was about 11 years old, my school had a spaghetti dinner fundraiser, a $1 meal to raise money for student activities. Sitting across from me at the table was what I thought was an old man (he was probably in his 30s) and he told me he spoke five languages and had been to 40 countries. On the spot, I decided: that’s the life I want to lead! And I managed to do that. So I’m a traveler, I’m a caring person. One of my ongoing projects is environmental. In Tanzania, I’ve been working with a village to plant trees. So far, we’ve planted 32,560.

Q: So, you want to help. People, the environment, everyone?

All my books really come from a sense of a big issue that’s affecting people’s lives. My very first book came out of the two and a half years I spent in Jerusalem managing the first significant U.S. government project to help Palestinians. Through that, I got to understand the multiple sides of that conflict. I decided to write a novel – later published as A Vision of Angels – that would, through fiction, reveal how the conflict affects ordinary people’s lives. The main characters were an Israeli war hero, an Arab Christian grocer, an American photojournalist, and a Palestinian farmer.

That sort of defined my other work as well. After that, I wrote a book where the story dealt with the issue of human trafficking. There’s a young girl who’s been trafficked, and it’s about what her life is like and someone who’s trying to help her. All my stories deal with big issues, social and worldwide concerns, but I concoct a suspenseful plot to keep readers interested. So my stories aren’t all about ‘message’. I show how these things really affect ordinary people who get caught up in them.

Q: You founded the Smith Prize for Political Theater, which, although no longer active, was a powerful initiative. Do you still see your writing as a form of activism, and is there a chance the prize might be revived in the future?

Yes, I definitely see my writing as a form of activism. It’s unfortunate that the Smith Prize is no longer happening. We had some very successful plays that went on to good productions. One Smith Prize playwright who went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama! But when the pandemic hit, it really devastated the theater world as you couldn’t have people gathered in enclosed spaces, and theater doesn’t work well over video calls. It just became time to let it go.

I’ve thought about bringing it back. But it’s a lot of work and right now, I’m focused on the Tanzania Trees Project. Maybe when I reach 100,000 trees, I’ll revisit the idea of political theater.

Q: So you have traveled across the globe. Can you tell us a bit about the countries that have shaped you the most?

The countries I’ve lived in have shaped me. I’ve probably spent about seven years total in Greece, so of course Greece is very important to who I am. I also lived in Jerusalem which was a deeply powerful experience. Then I spent a couple of years in Thailand, headquartered in Bangkok but working all over Asia. I was based there while serving as a financial advisor and analyst on every U.S. government project funded in Asia at the time. So I was constantly on the move.

One of those projects was in India. I had already traveled there personally, but for work, I began going to Mumbai about every six weeks for over a couple of years. India made a huge impression on me; the overwhelming poverty but also the country’s determination to move forward. That contrast really stayed with me.

I don’t think I mentioned Poland, but that experience also moved me deeply. I spent over two years there serving as an advisor for the World Bank to the new Minister of Finance following the collapse of the Communist government when Solidarity came into power. I was a housing finance advisor and helped to create Poland’s first-ever mortgage system, something that allowed people to borrow money to buy homes, instead of relying solely on savings.

I’ve also worked extensively across the U.S., especially in areas facing deep poverty. I did a lot of work with Native American communities and was involved with an agency that focused only on “special impact areas”, the 40 poorest areas in America. These were often rural counties or urban census tracts, frequently predominantly Black or Hispanic neighborhoods. All of these experiences—abroad and at home—have shaped how I see the world.

Q: Is there a wild or unforgettable experience from your life, something people should hear?

One story that stands out is from my work with Native American communities. I became familiar with the legal framework around treaties—or the rare absence of them—with most of the tribes. In Alaska, there was no treaty, and a law called the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act included a hidden time bomb: after 20 years, Native land, normally protected, would be taxed based on the value of its highest possible use. So, if there was oil under the land and it wasn’t being pumped out, indigenous Alaskans would still be taxed as if it were, which would have forced them to sell their land to pay taxes.

I brought this to the attention of the White House—President Carter specifically—and he issued an Executive Order to set aside that provision of the law. Because he had a Democratic Congress, that Executive Order was later turned into law, permanently protecting the sovereignty of Native Alaskan land. So yes, I’ve had the chance to impact people’s lives in meaningful ways.

Q: You’ve traveled and lived all over the world, and one of these places is also Santorini. You first lived there in the early ’70s, and you’ve been back recently. I know it’s hard to sum it all up, but how has Santorini changed since those early days?

When I first went to Santorini in 1972, I had no idea what the island looked like. I hadn’t even seen a photo. I was working for the National Center of Social Research (EKKE) in Athens, studying rural-to-urban migration, but city life didn’t suit me. So I convinced EKKE that I should go to the islands to assess the ‘push’ factors driving people to move to Athens. Through connections in Amfiali, near Piraeus, where many Santorini families had settled, I chose Santorini, sight unseen.

The ferry ride was a 20-hour journey, passing dry, barren islands like Ios and Naxos. I began to worry I was heading to a desert. Then Santorini appeared—volcanic cliffs, lush vineyards, completely unlike anything I expected.

There was no airport, hardly any tourism, and very few foreigners. I spent two winters there, often the only non-Greek person around. The villages were small and surrounded by open land—not the sprawl of villas you see now. I lived without hot water, taking a weekly shower in Fira for 25 cents at a hotel—ironically, the same one I stayed at on my recent visit.

Back then, Oia was abandoned and crumbling. Now, it’s one of the most photographed places on Earth. The caldera view remains breathtaking, but much of the island’s quiet magic has been lost.

Q: And, what is it that made you a Grecophile? After your time in Santorini, how has your relationship with Greece evolved over the years?

Well, I just fell in love with the Greek people, basically. They’re very hospitable and love to tell good stories. In my village, we didn’t have a television set for a long time—one finally arrived eventually—but before that, people would say, “Oh, let’s tell stories tonight.” So everyone would gather in a little spot, sit on the ground, and we would share stories and things like that. I loved all of that. It was great. And then, of course, the natural beauty of the country, it really is wonderful.

Q: Do you have any more stories set in Greece?

I’ve been thinking about it, and the answer is yes and no. Yes, I’d like to write something set in Greece again because it means a lot to me and I know it well enough to portray it authentically. But I’m not interested in writing a series with the same main character. I prefer each story to stand on its own.

If I can come up with a suspenseful story that includes social activism, something that keeps readers engaged without hitting them over the head with a message, I’d consider it. I haven’t ruled it out, but writing a book takes years, and I don’t have unlimited time. Still, I love the idea.

Q: Okay, so what’s unique about this book being set in Greece compared to other places you’ve written about?

Well, there’s just so many things about being Greek. The church, for example, plays a big role, which wouldn’t be the same elsewhere. Honestly, it’s hard to pin down one thing, but just being in Greece sets it apart from my other books.

The geography, the landscape, the culture, all of that shapes the story in ways that wouldn’t happen in other places. For example, in another book I wrote, Cooper’s Promise, I created a fictitious African town with an Arab diamond district. I combined different cultural elements to build that world because I hadn’t lived in one place long enough to capture it authentically. But with Greece, I know the place well.

With Fire on the Island, I wanted to tell a refugee story but ended up making it more of an homage to Greece and its people. The refugees didn’t really mingle much in my village—they had to move on quickly—but their presence stirred conflicts among the villagers. So the story became more about the Greeks than the refugees.

Later, I wrote Istanbul Crossing, a true refugee story where almost all the characters are refugees. I don’t know Turkish society deeply, so I focused on the human side, but with Fire on the Island, my familiarity with Greek culture really shines through.

Q: Are you working on something new, right now? If so, where is it set this time?

Yes, I’m working on a new novel. I’m not too far into it yet, but I’ve been thinking about it for quite a while. This one is set in America. I actually have the rather unique distinction of being a 16th-generation American, my family came over on one of the earliest ships after the Mayflower. So we’ve been in the country for about approximately 400 years. I’m very concerned about what’s happening in the U.S. these days. I want to write something that looks at that long legacy. What does it mean to come from 16 generations of Americans? Where has that brought us? It feels like a story I’m in a good position to tell, because I grew up with all these stories. One cousin was even what we’d call the "Man Friday" to Abraham Lincoln, meaning he served as his personal assistant/butler. So there’s this long, textured history in my head that I need to explore, and I think I’ve found a way to start shaping it into a story.

Of course, it will have an autobiographical element as all of my novels. All my main characters are, in some way, parts of me. Even when I’m combining or reshaping them, the emotional truth is always there. So yes, while the stories are fictional, they’re built out of real places, people, and things I’ve personally felt or seen.

Q: Fire on the Island has feminist elements, with strong women who are leaders, rebellious, and uncompromising. Was that intentional from the start, or did the characters evolve that way?

The women characters, especially the three generations in one family – the grandmother, her daughter and granddaughter, are based on real people. Their voices in the book come from real life. I gave them a fictional story, but the characters themselves are drawn from people I know, which is true for most of my characters. In Fire on the Island, having returned to the same village every year for 20 years, I got to know this family well. They weren’t offended by how they were portrayed; in fact, they’re proud to be in the book, even though I didn’t use their real names.

I think women have a very important part in Greek society in general. They’re very strong characters. In my time here, it was clear to me that the men controlled the fields, but the women controlled the village and the household. That strength is reflected in the story.

Q: Throughout the book, you sprinkle in Greek phrases that really ground the story. So, do you know Greek?

I didn’t know Greek when I first moved to Athens. Before going to Greece, I got a Greek tutor, but we didn’t get far. The only word I really learned was malaka (laughs).

The tutor mostly wanted to talk about girls, so it wasn’t very productive! But I’ve always liked studying languages and grammar. I taught myself Greek sto dromo (on the street) when I got to Greece, especially after moving to Santorini, where nobody spoke English in my village. I had to learn it.

I actually love Greek. It’s not a hard language for me. The hardest part for most people is there aren’t many cognates, no words that sound similar to other languages. Like in French, révolution means revolution, but the Greek word for revolution – epanastasis – doesn’t sound ljke any obvious word in English. So students of Greek have to learn a lot of new words.

Back when I lived on Santorini, I spoke well enough that people wouldn’t believe I’m not Greek. I don’t speak as well now, but thirty years ago, I really did.

Q: One last question: if you had to describe yourself, Greece, and Fire on the Island each with just one word, what would they be?

I’d say for myself: empathetic. I care about people, especially the disenfranchised and that has motivated drives what I do.

For Greece: welcoming.

I’d say for myself: empathetic. I care about people, especially the disenfranchised and that has motivated drives what I do.

For Greece: welcoming.

And the book? I’d say thoughtful. The story asks readers to think about tough issues, like being a stranger in a strange land, or topics like homosexuality in Greek society. These are difficult subjects for many people, and I wanted to explore them honestly in the book.

Thank you, Tim, for sharing your stories, your passion, and your heart with us. It’s been a pleasure getting a deeper look into the life behind Fire on the Island, and the purpose behind every page!

Thank you, Tim, for sharing your stories, your passion, and your heart with us. It’s been a pleasure getting a deeper look into the life behind Fire on the Island, and the purpose behind every page!

Want to learn more about Tim? Visit his website and grab your copy of Fire on the Island HERE!